I Was Just a Kid, Hanging Out at 2:30 AM, When I Watched a Car Full of Screaming Teens Plunge 20 Feet into a Black Gulf Coast River: The Terrifying 180 Seconds Where I Became a Hero… Or a Statistic? You Won’t Believe What the Darkness Whispered as I Fought the Current to Save Four Lives—Including the Cop Who Arrived to Save Me.

Part 1: The Abyss Swallowed the Light

My name is Elijah Walker. I’m 17. Two years ago, I was just Eli, trying to stay out of trouble in Bayou Vista, a forgotten sliver of the Gulf Coast where the humidity hangs thick enough to choke on and the Pascagoula River is less a landmark and more a hungry, black mouth. That’s where the story starts, or where the nightmare started, depending on how I look at it in the middle of the night now.

It was 2:30 AM. July. The air was a suffocating, damp blanket, smelling of salt, dead fish, and gasoline. I was sitting on the edge of the public boat ramp—the one everyone knows is slick with moss and a hazard even in daylight—just trying to clear my head. The moon was a sickly, half-eaten coin struggling to pierce the cloud cover. All I could see was the oily sheen of the water stretching out to the darkness, and maybe the cheap glow of my phone screen.

Then came the sound.

It wasn’t a roar, or a splash, not yet. It was a high-pitched, frantic engine whine, the sound of a small car being severely mishandled, followed by the shriek of tires fighting a losing battle against concrete and slick algae. The sound was too close. My head snapped up.

A beat-up silver sedan, moving way too fast, fishtailed wildly, its headlights momentarily blinding me as it slid down the ramp. I saw three terrified faces through the windows—girls, teenagers, maybe my age. They weren’t just driving; they were losing control, and the river was the only thing waiting for them.

My mind stuttered. Stop. Brake. Turn. But the car didn’t stop. It hit the end of the ramp with a sickening, grinding shudder that ripped through the quiet night like a gunshot. For a split-second, it seemed to hover, tail-lights blinking a final, desperate red warning. Then, with a colossal, violent KA-WHOOM, the Pascagoula River swallowed the entire front half of the sedan.

The screams came immediately. Not the panicked shrieks you hear in movies, but a primal, absolute terror—a sound so raw and desperate it felt like a physical blow to my chest. They were trapped. The car was already listing, water rushing into the cabin, pulling the metal deeper into the blackness. The entire incident, from the skid to the splash, couldn’t have taken more than five seconds.

I didn’t think. I couldn’t have. My body just reacted, a switch flipped from 17-year-old kid to something purely instinctual. The chilling reality hit me: if I waited for a siren, for help, for anyone else, those girls would be gone. Drowned. The river was merciless, and it was fast.

I tore off my shoes, stripped my t-shirt—the heavy, wet cotton would become an anchor—and I was sprinting. The air felt cold against my skin even in the humidity. As I hit the edge of the ramp, the cold, disgusting water of the river wrapped around my ankles, then my knees. It was colder than the air, thicker, and utterly, totally black. It hid its dangers well.

I looked out, maybe 20 feet from the shore. The back of the silver sedan was bobbing, sinking fast, its rear bumper tilting precariously. The currents were already tugging at me, an unseen, powerful hand trying to drag me downriver. The desperate screams were fading, turning into choked gurgles and splashes.

I took a deep, shaky breath, tasting the river air, heavy with decay. My adrenaline was a spike of white-hot fire, overriding the primal fear that was screaming at me to stop. I dove in.

The water closed over my head, a heavy, suffocating pressure. It was like swimming in ink. I couldn’t see my hand in front of my face. All sense of direction was gone, replaced by the relentless, churning push of the current. I kept my focus on the one thing I could still hear: the faint, frantic splashing near the sinking car. Get to them. Get to the sound.

I surfaced, gasping, spitting out the vile water. The car was barely a shape now, a shadow clinging to the surface. Two girls had managed to scramble onto the trunk, their bodies convulsing with cold and shock. The third was struggling, half-submerged, holding onto a broken piece of the back window. Her cries were the most heart-breaking.

I reached the car. The metal was shockingly cold. “Hold on!” I yelled, my voice thin and reedy against the vast, oppressive night. “My name is Eli! I’ve got you! Don’t let go!”

The girl closest to me, a blonde with wide, water-logged eyes, just stared, paralyzed. Her friend, tougher, maybe, whispered, “It’s sinking… we’re sinking!”

The trunk tilted again, a sickening lurch downwards. This was the point of no return. We were all going down together if I didn’t act now.

Part 2: The Weight of Four Souls

The problem wasn’t getting to them; the problem was convincing them that the danger was now behind us, and the swim to safety, the terrifying swim through the dark, churning water, had begun.

“Listen to me!” I shouted, gripping the blonde girl’s soaked sweatshirt with one hand, bracing myself against the sinking car with the other. “The car is going down. You have to let go and swim with me. Can you kick? Just kick!”

The girl, whose name I would later learn was Jessica, shook her head frantically. Tears and river water streamed down her face. She was frozen. I knew then that rational persuasion was useless. The shock had locked her up.

I made a terrible, instant calculation. The current was pushing the car down and away from the ramp. I needed to move fast. I gripped her tight, pulled her off the trunk, and immediately turned back toward the faint, barely visible glow of the shore lights. I was essentially towing her—kicking hard, dragging her dead weight, trying desperately to keep her head above the surface as the current tried to rip her from my grasp.

Every kick was a brutal effort. My lungs burned, and the darkness felt physical, pressing in on my eyes. I kept glancing back, and the silver sedan was already almost completely gone. Only the last foot of the bumper remained, and then, with a final bubble and gurgle, it was swallowed whole. Gone.

I got Jessica to the ramp, dragging her onto the slick, mossy concrete where she collapsed, coughing up water and shuddering violently. I didn’t pause. The other two girls were still out there.

The return swim was harder. The cold had seeped into my muscles. My arms felt like lead, and my legs were cramping. But the screams of the remaining girls—now closer to pure panic—drove me back. The first rescue had taken too long.

When I reached the second girl, Emily, she was thrashing, completely out of control. Her panic was dangerous; she grabbed onto my neck, forcing me underwater for a terrifying, heart-stopping moment. I fought up, sputtering, and had to brutally wrench her arms off, spinning her around and forcing her into a rescue tow—keeping her head elevated and facing the shore. I kept repeating, like a broken mantra, “Kick, Emily! Kick! We’re almost there!”

The swim back with Emily was a blur of exhausting struggle. I could taste the metallic tang of adrenaline and fear in my own mouth. I got her to safety, laid her next to Jessica, and turned for the third girl.

As I took the third deep breath, a siren finally broke the silence—a distant wail, getting closer. Too late, I thought. Always too late.

The third girl, Maria, was miraculously clinging to a floating piece of debris, exhausted but conscious. She was the one who was sinking before. I got to her quickly, and she was silent, utterly spent, offering no resistance as I towed her back.

I delivered Maria to the shore, dropping to my knees for a second, fighting the nausea and the total depletion of my energy reserves. My body was shaking so hard I could barely stand.

That’s when the second disaster struck.

Officer Mercer arrived in a flash of blue and red lights. He was a big guy, maybe mid-forties, and he was out of his squad car before it stopped rolling. He saw the girls, heard their sobs, and saw me, just a silhouette dripping wet and shivering.

He didn’t hesitate. He stripped his duty belt and vest, yelled into his radio, and plunged into the water where the car went down, thinking there might still be someone inside. He was a good cop, but he wasn’t a strong swimmer, and the current was unforgiving. He was also wearing heavy clothes and boots.

I saw him start to struggle. Not the flailing of a novice, but the frantic, head-bobbing desperation of someone who realizes, too late, that the water has won. His head would disappear, then reappear with a loud, hacking cough. The siren, the fear, the adrenaline—it all seemed to coalesce around him. He was panicking, fighting the current, and losing.

Are you kidding me? That was the only coherent thought I had. I just saved three people, and now I have to save the guy who is supposed to be the actual savior?

I looked at the three girls huddled on the ramp. They were safe. I looked at the dark water, where the officer was going under again, only 15 feet out. He was an adult. A policeman. A symbol of authority. But right now, he was just another human being drowning in the black water.

Exhaustion was a physical pain, a crushing weight in my chest. My muscles screamed a full-volume NO. But the image of his head going down one last time—that was enough. It was the same soundless, terrifying image as the silver sedan.

I forced myself back in. The shock of the cold water was almost unbearable this time. I swam toward him, my strokes weak and ragged, relying purely on the last, desperate fumes of adrenaline.

When I got to him, he was barely conscious, thrashing wildly. I had to use every ounce of what little strength I had left. I approached him from behind, hooked my arm securely under his armpit, and rolled onto my back. This was textbook lifesaving, the move my uncle, a former Coast Guardsman, had shown me a thousand times in a calm pool.

The officer was heavier than the three girls combined, and his soaked uniform felt like chainmail. I had to fight his instinctive, panicky grab for my neck, shouting over and over, “I’m Eli! I got you, Officer! Stop fighting! I’m taking you in!”

That voice—the sound of a calm, controlled teenager—seemed to penetrate his shock. He went momentarily limp, trusting the voice he couldn’t see. I began the grueling, agonizing tow back to the ramp. It felt like I was moving through mud, not water.

When I finally reached the concrete ramp and dragged the nearly comatose Officer Mercer onto the edge, I didn’t have the strength to stand. I didn’t have the strength to even speak. I just collapsed next to him, shivering uncontrollably, spitting water, staring up at the flashing, apocalyptic red and blue lights that had finally multiplied, illuminating the scene.

I had saved four lives. But the only thought that repeated in my mind, an echo of the fear, was: What if the car had only needed me to save two? Would I have been too tired for the officer?

The burden of being called a ‘hero’ is that you never stop playing the ‘what if’ game. That night, the black water of the Pascagoula taught me that the hero isn’t the one who acts without fear. The hero is the one who acts despite the knowledge that the darkness is hungry, and that the risk of becoming a statistic is always, terrifyingly real. My life changed in 180 seconds. I don’t see the river anymore. I see the darkness, and I hear the silence that followed the final splash.

News

My Mom Cleaned His Mansion for 20 Years. I Defended His ‘Weak’ Son in the Cafeteria. What That Billionaire Did When He Found Out Left Us Breathless—And Not in the Way You Think.

Part 1 There are two rules in my life. Rule number one: We are ghosts. My mom, Elena, taught…

They Fired Me For Helping a ‘Homeless’ Old Man Everyone Ignored. They Laughed When I Said His Name. Now I Run His Billion-Dollar Foundation. This is The Story They Don’t Want You to Know.

(Part 1) The cold wasn’t just a temperature; it was a monster. It was the kind of cold that finds…

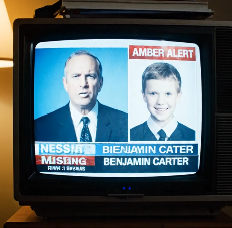

THE MAID’S DAUGHTER WHO DEFIED A BILLIONAIRE’S CODE: How a Lost, Freezing Child in a Gut-Wrenching Alleyway Stared Into My Soul, Forcing Me to Choose Between Saving My Mother’s Life and Job, or Upholding My Late Father’s Sacred Military Oath to Never, EVER, Leave a Man Behind—A Suspenseful, True Story of Fear, Family, and an Amber Alert That Shook a City to Its Core, Revealing the Dark Secret Behind One of America’s Wealthiest Families.

Part 1 My name is Elias Vance, and I grew up on a sharp edge. The kind of edge…

THE SCYTHE OF SILENCE: Sergeant Alex “Reaper” Riley’s Uncensored Confession of the Mission They Gassed—How We Encountered the War’s True Undead in “Sector 4,” Where American Soldiers Weren’t Killed, But Unmade, And The Scariest Sound Wasn’t Gunfire, But The Primal Scream That Followed.

The fear you feel when a bullet cracks past your ear—that’s a quick, clean fear. It has a shape, a…

The Nightmare of the Watcher: Why I Left My Brother Bleeding on a Sun-Scorched Alleyway, a Decision That Saved a Squad But Condemned My Soul—The Unspeakable Truth Behind ‘Never Leave a Man Behind’ When Command Forces You to Choose Which Life to Sacrifice and the Aftermath of a Scar That No Medal Can Ever Cover. How the Fire of Command Shattered the Soul of Sergeant Alex Riley in Al-Nujum.

The heat didn’t just radiate in Al-Nujum; it pressed down, a physical, suffocating weight that tasted like dust and fear….

The Green-Eyed Ghost of Helmand: A Marine’s Confession of the Unspeakable Choice That Saved My Squad But Damned My Soul—The Ten-Foot Shadow That Only Appears When the Guilt is Loudest, Revealing the True, Cannibalistic Horror Lurking in the Fog of War. You Won’t Believe What I Had to Leave Behind to Survive.

My name is Jake Riley. They called me “Bull” for a long time. Not because of my temper, though I…

End of content

No more pages to load