I am Walter Jenkins. Wally to my friends. I built my life with calluses on my hands and rust in my joints, pouring forty years into the assembly line at the old Northwood plant, breathing in dust and promises. Promises that one day, my wife, Eleanor, and I would finally live. Now, she’s gone, and all that’s left is me, a six-figure savings account, and a sense of duty that threatens to devour my last, best chance at peace.

Part 1

The day I finally cashed out my 401(k)—the lump sum I’d been waiting for since 1985—I felt lighter than I had since I was a teenager. It wasn’t just the money; it was the freedom. $800,000. It represented every skipped vacation, every overtime shift on Christmas Eve, every cheap suit and dented Ford I’d ever owned. This wasn’t just savings; it was my life’s blood, distilled.

I was 67. The doctors had given me the boilerplate speech about “taking it easy,” but the real warning had come from my own body: the persistent ache in my back, the way my breath hitched on the second flight of stairs. It was a ticking clock. I had a vision: a small, sturdy RV, the open road, Eleanor’s favorite blues music playing softly, a simple life without the suffocating weight of obligation.

But Eleanor wasn’t there. She’d passed three years ago, a victim of the very same factory’s slow, toxic kiss. Now, the obligation wasn’t from the outside world; it was from within my own home, a pressure that came with the voices of my two grown children, Michael and Sarah.

I gathered them for a family meeting, a solemn affair in the dining room with the chipped Formica table. They sat across from me, Michael, 41, with his “entrepreneurial” dreams that bled money, and Sarah, 38, with her two beautiful, demanding kids and a mortgage that was a millstone around her neck.

“Kids,” I started, the cash account statement folded neatly in my hand, “I’m 67. Your mother and I worked our fingers to the bone so you could have a life better than ours. And you do. Now, it’s my turn.”

I saw the flicker. The look. It was a practiced expression of dutiful concern, but behind their eyes, I saw the raw, unmistakable gleam of avarice. It was a look I recognized from predatory salesmen, but seeing it on the faces of my own flesh and blood was a cold shock that traveled straight to my heart.

Michael, always the first to pounce, leaned forward, a sickly-sweet smile plastered on his face. “Dad, that’s beautiful. Absolutely beautiful. We’re so proud of you. But, look, I’ve been thinking about your legacy.”

He didn’t need to finish. The word—legacy—was just a thinly veiled code for my money.

Part 2

The suggestion was immediately laid out, like a trap sprung in slow motion. Michael needed a $150,000 “seed investment” for a “sure-fire” mobile app that would revolutionize dog walking. Sarah, meanwhile, had been “pre-approved” for a refinancing package on her house, but only if I would co-sign, essentially guaranteeing the half-million-dollar loan with my retirement fund.

Their pitches were rehearsed, laden with emotional blackmail and thinly veiled resentment.

“Dad,” Sarah said, her voice trembling—a performance I knew too well—”We just need a little help to get on our feet. For your grandchildren. Don’t you want to see them grow up in a house with a decent yard? Your money is just sitting there. You’ve earned the right to see it work.”

Work. It had worked enough. It had worked for forty goddamn years.

I looked at them, and a bitter, painful clarity washed over me. This was the moment of truth. This was the point where I became either the patriarch—the boundless ATM—or a ghost of a man who finally decided to live for himself.

“No,” I said, the single word cutting through the tense silence like a razor wire. It was a tremor in my own voice, the first sound of my own independence I’d made in decades.

Michael’s face hardened. “No? Dad, this is a chance to quadruple the money! You’re going to put that eight hundred grand under a mattress and let inflation eat it up? That’s not smart, Dad. That’s reckless.”

“Reckless?” I stood up, the chair scraping loudly across the wooden floor. My hands were shaking, not from fear, but from a lifetime of suppressed anger. “Reckless was working every holiday for you two to go to college. Reckless was pulling doubles when your mother was sick so we wouldn’t lose the house. This,” I tapped the statement on the table, “is not an investment portfolio. It is my exit strategy.”

The next few weeks were a psychological war zone. My phone rang constantly, a relentless symphony of guilt-tripping and thinly disguised demands. They brought the grandchildren over, holding them up as emotional shields. “Say goodbye to Grandpa, sweetie,” Sarah would coo, “because he won’t be around much if he doesn’t have the money to help us keep our house.”

They were treating me like a fool, an old man whose purpose had expired with his paycheck. They operated under the disgusting assumption that my sacrifices were their inheritance, that I had no right to enjoy the fruits of my labor if they were in need. The thought, “there is nothing more disgusting than a son or daughter-in-law coming up with great ideas to spend their hard earned savings,” repeated in my mind like a desperate mantra.

I remembered the advice I’d read, the old-timers who’d warned me: Don’t save it for those who have no idea the sacrifices you made to get it.

It was time to choose. The old Wally, the one who lived to serve, or the new Wally, the one who lived to live.

I started small. I bought myself a custom-made suit—expensive wool, tailored fit, the kind of suit I’d always told myself was “too much.” I felt foolish and triumphant simultaneously. Then, the real act of defiance: I began looking at RVs. Not the cheap, leaky ones, but the best. The most beautiful.

When I told Michael and Sarah I was buying a $200,000 Class A motorhome, their reaction was explosive. Michael accused me of having a “mid-life crisis.” Sarah burst into tears, accusing me of caring more about a metal box on wheels than her children’s future.

“I am enjoying my life, Sarah,” I said, my voice steady, feeling a strength I hadn’t possessed in years. “I cared for you for many years, and I taught you what I can. You had education, food, shelter, and support. Now it’s your responsibility to make your own money. I gave you the blueprint. Now, build your own damn house.”

It was the hardest, most necessary break of my life.

I scheduled a doctor’s appointment—a full check-up. The doctor confirmed the wear and tear but encouraged the plan. “Stay active, Wally. Moderate exercise. Travel. Don’t stress.”

I bought the RV. It was a beautiful machine, cream and deep blue, smelling of new leather and freedom.

The final, decisive moment came two weeks later. Sarah sent me a four-page email, a document of pure, distilled resentment, detailing every flaw she perceived in my parenting and every dollar she felt she was owed. She ended it by saying I was “bitter” and “selfish” and that I’d be “dying alone in a gas station parking lot.”

I felt the familiar spike of pain, the urge to retreat, to apologize, to fix it.

Then I read the line again: Some people embrace their golden years, while others become bitter. Life is too short to waste days on sad moments.

I walked outside, took a deep breath of the cool, autumn air, and got into my new RV. I looked at the letter, then at the open road ahead of me. I deleted the email, blocked their numbers, and drove.

I didn’t drive away from my kids; I drove to myself.

The first six months have been a revelation. I wake up, walk, read the newspaper online, and talk to people—politely, without complaint or criticism. I found an old friend, Billy, on Facebook, and we had coffee in Arizona. I’m learning to cook for one. I’m learning to be happy.

I still have half a million dollars. I still have my health, better than it was when I was stressed out of my mind. And I have peace. The guilt surfaces, a quick, familiar sting, but it’s quickly replaced by the profound, deep satisfaction of self-preservation.

I am Walter Jenkins. I am 67. And for the first time in my life, I am free. The money is mine. The life is mine. And my only job now is to enjoy it, for as long as I can, with the joy of a man who finally won the war for his own soul.

News

My Mom Cleaned His Mansion for 20 Years. I Defended His ‘Weak’ Son in the Cafeteria. What That Billionaire Did When He Found Out Left Us Breathless—And Not in the Way You Think.

Part 1 There are two rules in my life. Rule number one: We are ghosts. My mom, Elena, taught…

They Fired Me For Helping a ‘Homeless’ Old Man Everyone Ignored. They Laughed When I Said His Name. Now I Run His Billion-Dollar Foundation. This is The Story They Don’t Want You to Know.

(Part 1) The cold wasn’t just a temperature; it was a monster. It was the kind of cold that finds…

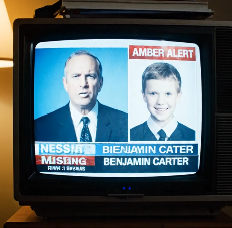

THE MAID’S DAUGHTER WHO DEFIED A BILLIONAIRE’S CODE: How a Lost, Freezing Child in a Gut-Wrenching Alleyway Stared Into My Soul, Forcing Me to Choose Between Saving My Mother’s Life and Job, or Upholding My Late Father’s Sacred Military Oath to Never, EVER, Leave a Man Behind—A Suspenseful, True Story of Fear, Family, and an Amber Alert That Shook a City to Its Core, Revealing the Dark Secret Behind One of America’s Wealthiest Families.

Part 1 My name is Elias Vance, and I grew up on a sharp edge. The kind of edge…

THE SCYTHE OF SILENCE: Sergeant Alex “Reaper” Riley’s Uncensored Confession of the Mission They Gassed—How We Encountered the War’s True Undead in “Sector 4,” Where American Soldiers Weren’t Killed, But Unmade, And The Scariest Sound Wasn’t Gunfire, But The Primal Scream That Followed.

The fear you feel when a bullet cracks past your ear—that’s a quick, clean fear. It has a shape, a…

The Nightmare of the Watcher: Why I Left My Brother Bleeding on a Sun-Scorched Alleyway, a Decision That Saved a Squad But Condemned My Soul—The Unspeakable Truth Behind ‘Never Leave a Man Behind’ When Command Forces You to Choose Which Life to Sacrifice and the Aftermath of a Scar That No Medal Can Ever Cover. How the Fire of Command Shattered the Soul of Sergeant Alex Riley in Al-Nujum.

The heat didn’t just radiate in Al-Nujum; it pressed down, a physical, suffocating weight that tasted like dust and fear….

The Green-Eyed Ghost of Helmand: A Marine’s Confession of the Unspeakable Choice That Saved My Squad But Damned My Soul—The Ten-Foot Shadow That Only Appears When the Guilt is Loudest, Revealing the True, Cannibalistic Horror Lurking in the Fog of War. You Won’t Believe What I Had to Leave Behind to Survive.

My name is Jake Riley. They called me “Bull” for a long time. Not because of my temper, though I…

End of content

No more pages to load