Part 1: The Choice that Defied the Rain

The thunder came at midnight, but it wasn’t from the sky. It was a mechanical, seismic roar that didn’t just shake the ground; it rattled the very core of who I thought I was. I felt it through the metal frame of my wheelchair, through the cheap foam mattress of the camping cot, through the duct-taped wooden boards that had become the only predictable structure in my unpredictable life.

I’m Ethan Cooper. I was sixteen, paralyzed from the T12 vertebra down since I was twelve. For eight months, my bedroom had been an eight-by-ten-foot covered porch on Riverside Drive in Portland, Oregon.

The four years since the accident that killed my parents and shattered my spine had been a relentless cycle of displacement. Doctors had described my condition with clinical precision—paraplegia, high needs, specialized placement required. But the foster system used a different language: liability, inconvenience, too much work. I’d cycled through six homes. Each one began with soft smiles and assurances, and each ended when the families realized that “accessibility” meant more than just good intentions. It meant ramps, expensive bathroom modifications, and a patience that inevitably exhausted itself against the daily reality of caring for a disabled teenager.

Carol Martinez, my current foster mother, was a single mother already struggling to raise three biological children in a cramped two-bedroom house. She meant well. I knew she meant well. But good intentions didn’t conjure up space, or money, or the structural changes required to make her small bathroom accessible. So, I slept on the porch, under a thin tarp when the rain was heavy, used a portable urinal that Carol emptied without complaint, and ate dinner on whatever surface was available, often my lap, because the kitchen table sat too high for my chair. I lived in a state of hyper-visibility—watched constantly by teachers trained to spot liability—yet utter invisibility to my peers, who had learned to look right through me.

This night, the sound was too powerful to ignore. The vibrations traveled up my spine into my chest, settling somewhere near my heart, where hope and a cold, sharp terror became indistinguishable. As I rolled closer to the porch railing, the spectacle resolved itself: 420 motorcycles lined the street in perfect, black formation, stretching beyond my line of sight in both directions. Their headlights, blindingly powerful, cut through the inky October darkness like search beams, hunting for something sacred. Men and women, clad in heavy leather, patches, and beards, moved with a disquieting military precision, unloading lumber, industrial-grade tools, and materials I couldn’t possibly identify. It looked like a siege.

Carol stood framed in the doorway behind me, a figure of frozen shock. Her hand was pressed against her mouth, her eyes wide with an emotion I’d never seen on her perpetually exhausted face. “Ethan,” she whispered, the sound cracking. “What did you do?”

But I knew exactly what I’d done. Sixteen hours earlier, on a rain-soaked street corner in this very city, I had made a choice—a purely instinctual, reckless choice—that defied every lesson the world had tried to teach me about my own physical limitations and value. I had abandoned my means of mobility, my independence, in a torrential downpour, to save a dying stranger.

The Relentless Rain

Rewind to six hours before midnight. Rewind to the rain. The October afternoon had arrived gray, heavy, and unforgiving. This was Portland rain: not the romantic drizzle you see in movies, but a relentless, soaking deluge that turned the streets into shallow, deceptive rivers.

I navigated the sidewalk along Powell Boulevard with the practiced, efficient proficiency of someone for whom every inch of progress is earned. My wheelchair wheels sliced through the deepest puddles, my cheap plastic poncho—Carol’s three-month-old attempt at weatherproofing—was soaked through, clinging coldly to my clothes. I was heading home from Jefferson High, where I’d spent seven hours being simultaneously invisible and hyper-visible.

My backpack, secured awkwardly across my lap because my chair’s back support couldn’t accommodate proper straps, held the homework I would complete that evening. I used the public library’s computers during the two hours before closing, the staff pretending not to notice that I was essentially loitering because my “home” had no adequate space. Achievement was the only currency I possessed. Giving up wasn’t an option; it was a luxury I couldn’t afford.

The rain intensified as I reached the intersection of Powell and 82nd Avenue. The traffic lights swayed slightly in the wind, which carried the sharp, biting scent of approaching winter. I waited for the crossing signal, water dripping from my hair into my eyes. My hands were already cramped from gripping the push rims for the forty-minute journey from school.

That’s when I heard it. A sound that cut through the monotonous urban symphony of traffic and relentless rain. A groan—low, agonized, and utterly out of place—coming from the bus shelter fifteen feet to my right.

I turned my head, squinting through the sheeting rain that reduced the world to impressionistic, gray blurs. Someone was sitting hunched forward on the bus shelter bench, one hand pressed hard against their chest. Even from this distance, even through the weather, I recognized the posture. This was beyond ordinary discomfort. This was serious distress.

My mind immediately flashed through the well-worn script of public non-intervention: Look away. Assume someone else will help. It’s not your responsibility. Getting involved complicates a life that is already too complicated. Most people prioritize their own discomfort over a stranger’s suffering.

But four years of being the person everyone looked past had taught me a grim, vital lesson: indifference kills. I had seen people walk past me when I’d fallen from my chair, when I’d struggled with an inaccessible door, when I’d needed thirty seconds of inconvenience from them. I couldn’t participate in that indifference now. I had never been most people.

I maneuvered my wheelchair toward the shelter, angling around a puddle that would have been impossible at full depth, my arms burning with the sudden, necessary effort. The figure on the bench became clearer: an older man, perhaps sixty-five or seventy, with a thick gray beard and a massive, worn leather jacket. His face was contorted in a pain that transcended a simple headache or fatigue.

“Sir,” I called out over the rain’s percussion. “Are you okay?”

The man looked up, his eyes unfocused, swimming in panic. His skin was an alarming, pale shade of ash. He tried to speak, but only managed a gasping, choked sound that sent a spike of ice through my chest. This was a medical emergency. A cardiac event.

“I’m calling 911,” I announced, reaching instinctively for my phone—the cheap, basic model Carol’s case manager provided for emergencies, with limited minutes and no data plan.

The man shook his head violently, then gasped again, his hand clutching his chest with desperate pressure. Words finally emerged, barely audible: “Pills? Jacket pocket. Can’t reach. Cardiac medication.”

He needed medication and the pain had locked his body into crisis. I made a calculation that felt insane, a snap judgment made in the space between heartbeats. The bus shelter bench was a standard eighteen inches off the ground. My wheelchair seat was twenty inches off the ground. If I positioned correctly, if I leveraged my upper body strength perfectly, if I compensated for the total lack of core stability that my paralysis created, I could reach his jacket pocket.

But it would require a total and terrifying sacrifice. It meant leaving my wheelchair—my independent existence—in the rain, transferring my entire, useless lower half onto the wet, treacherous bench, and trusting that, by some miracle, I could get back into the chair afterward. This process was difficult, even in my physical therapist’s safe, padded room. In a downpour, with no assistance, and a dying man beside me, it was potentially impossible.

Most people would have called 911 and stayed safely in their chair, maintaining the boundary between helper and helped. But I understood something that able-bodied people rarely grasped: my vulnerability created an obligation. Having nothing meant I had nothing left to lose. The most important moments in life required choosing someone else’s survival over my own comfort.

I locked my wheelchair’s brakes. I reached for the edge of the wet bench. My arms screamed as I executed a violent lateral transfer. My hands gripped the bench’s edge, my arms bearing my full weight, my torso swinging across the gap between the chair and the bench with a practiced, desperate efficiency. I landed inches from the man, immediately soaked to the skin. My legs were useless, but my hands were functional. I was completely dependent on a wooden bench, a bus shelter roof, and a dying stranger.

“Which pocket?” I demanded, already reaching toward the man’s heavy leather jacket.

He gestured weakly toward his right side. My cold, shaking fingers struggled with the zipper, finding the interior pocket. I extracted a small pill bottle. The label confirmed my grim guess: Nitroglycerin sublingual tablets. For angina and heart attack symptoms.

“How many?” I asked.

He held up one finger. I shook a single tablet into my palm and, remembering the basic first aid I’d learned during rehabilitation, placed it under the man’s tongue.

He closed his eyes. His breathing was still terribly labored, but slightly less desperate as the medication began its work. “Ambulance is coming,” I lied, knowing my phone was still secured to my backpack, which was strapped to my wheelchair—three feet away, a distance that might as well have been three miles.

We sat together in the relentless rain, a paralyzed teenager and a dying man, connected by a choice that was absurd in its recklessness and profound in its necessity. I counted the seconds, watching the terrifying gray slowly bleed from his skin, replaced by a pale, slightly more stable color. The vice-grip on his chest gradually loosened.

After ninety seconds, his breathing stabilized enough for speech. “You’re in a wheelchair,” he rasped, his voice rough.

“Was,” I corrected, the hysterical laugh I’d suppressed finally escaping. “Currently on a bench.”

His eyes focused fully for the first time, taking in my soaked form, the abandoned wheelchair, the absurdity of the scene. Shock, then recognition, then an intense, almost painful emotion I couldn’t identify shifted in his expression. “You left your chair to help me.”

“You were dying. Seemed more important than staying dry.”

“How are you going to get back?”

“Excellent question,” I admitted. “I’m hoping you’ll feel good enough to push my chair closer in a few minutes. Otherwise, this is going to be embarrassing.”

Then, impossibly, he smiled. A genuine, powerful smile. “What’s your name, kid?”

“Ethan Cooper.”

“Theodore Morrison. People call me Thunderhead.” He paused, gathering his immense strength. “You just saved my life, Ethan Cooper.”

“I just gave you a pill from your own pocket.”

“No,” Theodore’s voice grew stronger, more certain. “You made a choice. You sacrificed your mobility, your independence, to help a stranger. That’s not small. That’s extraordinary.” He dismissed my discomfort with the praise, understanding the true weight of the action better than I did. I had simply done what the situation required.

After five agonizing minutes, Theodore felt strong enough to stand carefully, supporting himself on the bus shelter’s frame, and push my wheelchair closer. The transfer back was arduous. My wet clothes and cold muscles made every movement precarious, but I managed it, settling back into my chair with a rush of relief so intense it felt like a narcotic.

“I owe you,” Theodore said, his voice carrying a weight that transcended mere gratitude. “And I always pay my debts.”

“You don’t owe me anything. I’m just glad you’re okay.”

He looked at me with an expression that felt almost sad, almost prophetic. “Kid, you have no idea what you just did, but you will. I promise you that.”

He left when the next bus arrived, walking carefully but steadily. I resumed my journey home, arriving at Carol’s forty minutes later, soaked and shivering, thinking about the strange intensity in Theodore Morrison’s eyes and the heavy promise he had left me with. I had no idea that six miles away, Theodore was making phone calls that would change everything.

Part 2: The Eruption of Compassion and the Impossible Legacy

I arrived back at Carol’s house, navigating to the porch—my bedroom, my territory, the only ten square feet of autonomy I possessed. Carol brought towels, dry clothes, and eventually dinner. I changed behind the sheet she had hung for privacy, dried myself as best I could, and settled into the camping cot. Rain drummed against the porch roof, the sound mocking Carol’s efforts to seal the gaps with duct tape. Exhaustion won. I fell asleep thinking about Theodore Morrison’s promise, about debts and obligations, and the way gratitude could feel heavy as prophecy.

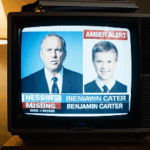

Unbeknownst to me, six miles away, Theodore “Thunderhead” Morrison was activating a network forty-three years in the making. He was the founder of the Hell’s Angels Pacific Northwest chapter, a man who, like me, had been dismissed by institutions and built his life on a code of fierce loyalty and protection of the vulnerable.

He told his wife, Margaret, about the attack: “I thought that was it, Maggie. I thought I was done.” He told her about me: “A kid in a wheelchair left his chair in the rain to give me my own medication because I couldn’t reach it myself. He sacrificed his mobility, his independence, to save a stranger. No hesitation. Just saw someone suffering and acted.”

Theodore spent the next four hours making calls, activating the network that connected chapters across Oregon and Washington. He called Victor “Ironside” Chen, the chapter president, and members who worked in construction, healthcare, and social services. By 10:00 p.m., he had a complete picture of my life: sixteen years old, paralyzed at twelve, bounced through six foster homes, maintaining a 3.8 GPA despite sleeping on a front porch with no accessible bathroom. The kid who’d saved his life was essentially homeless, failed by the very system designed to protect him.

Theodore’s rage crystallized into an iron purpose. This was the precise injustice the Hell’s Angels existed to address: the vulnerable being failed, the deserving being overlooked, the brave being punished by circumstance.

He called Victor Chen at 10:30 p.m. “We need an emergency assembly, Victor. Every member who can ride. I want to overwhelm this response. I want 400 bikers showing up at midnight with enough lumber and tools to build a structure that actually protects him. I want this kid to wake up and understand that his choice mattered, that heroism gets celebrated, that the world contains people who give a damn.”

“Thunderhead,” Victor cautioned, “that’s going to be highly visible. It’s going to make news.”

“Good. Let people see who we actually are. Let them see what happens when real bikers encounter real courage.” Theodore’s voice intensified with the weight of decades of leadership. “This kid saved my life, Victor. He’s sixteen years old, sleeping on a porch, and despite all that, he chose compassion. That deserves everything we can give.”

The machinery activated instantly. Phone calls spread through the network like electrical current. Resources meant for the annual charity ride were immediately redirected. By midnight, 420 Hell’s Angels members were preparing for a ride to Riverside Drive.

The Midnight Thunder and the Miracle of Construction

I woke abruptly at 11:45 p.m. to the sound of distant thunder—mechanical, rhythmic, growing steadily louder until it became an impossible, deafening wall of noise. I leveraged myself into my wheelchair, heart pounding, and rolled to the edge of the porch.

What I saw defied comprehension. Motorcycles, 420 of them, lined the street in perfect, intimidating formation, stretching beyond my line of sight. Men and women in leather moved with terrifying, coordinated purpose, unloading massive quantities of lumber, pre-fabricated walls, tools, and construction materials from a fleet of pickup trucks. The construction work lights they set up turned midnight into a harsh, artificial day.

Carol appeared in the doorway, her three younger children huddled behind her. Her breath hitched in her throat. We watched, silent and paralyzed by the sheer spectacle.

Then, Theodore Morrison walked toward the porch. He looked stronger than he had at the bus stop, his presence commanding the chaos. Even before he spoke, I recognized him.

“Hello, Ethan,” Theodore said, his voice carrying clearly over the roar of the idling engines and the bustle of work. “Told you. I pay my debts.”

My brain struggled to form a coherent thought. “I… I don’t understand.”

“You saved my life,” Theodore repeated, his gaze unwavering. “You left your wheelchair in a rainstorm to help a dying stranger. You chose my survival over your own comfort. We’re the Hell’s Angels Pacific Northwest chapter. And when someone shows the kind of courage you demonstrated, we respond.”

He gestured to the surrounding, organized chaos. “We’re here to build you a shelter. A real shelter. Something weatherproof, accessible, with proper facilities. Something that honors what you did.”

“I just gave you your medication,” I protested, echoing my earlier attempt to minimize my action.

“No, you made a choice that most people wouldn’t make. You demonstrated that character exists independent of circumstance. That heroism has nothing to do with physical ability. That the most valuable humans are often the ones society overlooks.” Theodore’s voice grew profound, authoritative. “We see you, Ethan. We see your courage, and we’re going to make sure you never sleep in the rain again.”

Carol was crying openly, one hand pressed against her mouth. Neighbors, drawn by the incredible noise and lights, peered from their windows, witnessing a phenomenon that would be discussed for years.

Then the work began. Four hundred and twenty Hell’s Angels members and supporters worked through the night with an efficiency that bordered on the supernatural. They were not just a motorcycle club; they were electricians, plumbers, architects, carpenters, and construction managers. The sheer number of hands, combined with their coordinated focus, meant that the laws of physics and time seemed suspended.

The design had been created by a member who worked as an architect, refined by others who specialized in accessibility. It was not a shed. It was a 16×20 ft fully functional tiny house being constructed in Carol’s backyard—pre-fabricated walls locking together like massive puzzle pieces, a durable metal roof designed specifically for Portland’s rain, electrical wiring, heating, and plumbing for a small, fully accessible bathroom.

I sat on the porch in my wheelchair, watching in disbelief. Members periodically approached me, treating me not like a charity case, but like the client whose specifications were paramount. They asked about my specific needs: counter height preferences, door width requirements, light switch positioning. They treated my disability not as an inconvenience, but as the central, defining feature of the design.

Tommy Shaw, a member who had sustained a spinal cord injury in a motorcycle accident five years prior and now used a wheelchair himself, spent an hour discussing accessibility features with me. “We are building this right, Ethan,” Tommy said, his voice firm and absolute. “No half measures. No ‘good enough.’ You deserve a space that actually works, that gives you independence, that treats your needs as central rather than peripheral.”

The bathroom took shape first: a roll-in shower with a built-in seat, a raised toilet with strategically placed grab bars, a sink at the perfect height. Then the sleeping area with a bed frame designed for easy lateral transfers, accessible storage, and logical electrical outlets. By 3:00 a.m., the structure was largely complete. By 5:00 a.m., members were adding the finishing touches, transforming the functional space into a welcoming home.

Theodore found me around 5:30 a.m. as dawn was beginning to break over the eastern sky. “Want to see your new home?”

I rolled my wheelchair down a freshly installed, perfectly sloped, and properly secured ramp and approached the structure that had materialized from the darkness. The door opened smoothly, wide enough for comfortable access, leading into a space that felt impossible. Everything was positioned perfectly, designed not around the convenience of the able-bodied, but around my needs. Light switches were reachable. The desk had proper clearance. I could maneuver without constantly bumping walls.

“This is… mine,” I managed, the words catching in a sob. Four years of internalized self-doubt, of feeling like a burden, of accepting indignity, fractured under the weight of this impossible grace.

“This is yours,” Theodore confirmed. “Designed for you, built for you, given to you because you demonstrated courage that deserves recognition. We don’t let heroes sleep in the rain.”

Carol appeared beside me, her own tears flowing freely. “Ethan, they also brought money for modifications to the main house. They’re going to make the bathroom accessible, widen doorways, install ramps. They’re going to make it so you can actually live here, not just survive here.”

The Impossible CPR and the Foundation

The sun rose over Portland, illuminating the structure that stood in Carol’s backyard like evidence of an impossible miracle. News crews arrived, capturing the footage that would explode across national media. Theodore stood before the cameras, explaining the cardiac episode and the wheelchair-bound teenager, his voice carrying the authority of a man who understood real valor.

“The world judges people by appearance,” Theodore told the cameras. “Sees a kid in a wheelchair and makes assumptions about capability. But character exists independent of physical form. Courage has nothing to do with whether you can walk. This kid demonstrated more heroism in fifteen minutes than most people show in a lifetime. He deserves a home.”

The story went viral instantly. But for me, the most meaningful moment came around 7:00 a.m., after most of the bikers had departed, and only Theodore remained. We sat in my new space, Theodore in a chair positioned at conversational height, surrounded by the impossible reality of what had occurred.

“Why did you do this?” I asked, still overwhelmed. “It’s too much. It’s disproportionate. I just helped you reach your medication.”

“You left your wheelchair in a rainstorm to save a dying stranger,” Theodore said firmly. “You sacrificed your independence because my survival mattered more than your comfort. That’s not small. That’s extraordinary. And it revealed something I needed to see: that the most important humans are often the ones society dismisses.”

He revealed the next step: “We’re establishing a foundation, the Thunderhead Accessibility Initiative. It will fund modifications for people with disabilities, support inclusive housing, and advocate for better systems. We’re using this moment as a catalyst to do the work we should have been doing all along.”

Three days later, the miracle became medically absurd. Theodore received a call from his cardiologist, Dr. Patricia Hammond. “Theodore, I reviewed the tests from your recent episode. According to these readings, you had a full cardiac arrest, not angina. Your heart stopped completely for approximately ninety seconds. You should be dead or severely brain damaged.”

Theodore’s chest seized again, this time with shock. “That’s not possible. I was conscious. The medication worked.”

“Nitroglycerin doesn’t restart stopped hearts. Only CPR or defibrillation can do that.” Dr. Hammond paused, her voice cautious. “Theodore, I think this teenager might have performed CPR without realizing it. He literally brought you back from death.”

The kid in the wheelchair, the one sleeping on a porch, had performed a medical intervention that prevented Theodore’s death, doing it without training, using only his upper body strength and whatever pure instinct had guided his actions during those ninety seconds.

Theodore called Victor Chen immediately. “We need to expand what we’re doing for Ethan. He didn’t just help me. He saved me from actual death. We need to make sure he understands his value, his capability, his extraordinary nature.”

The Hell’s Angels network activated again. They arranged for me to receive formal medical training—CPR certification, first aid—formalizing the instincts I had demonstrated. They connected me with disability advocacy groups and mentors. I became, inadvertently, famous.

Six months after that October night, my life felt surreal. I volunteered with the Initiative, helping Theodore identify and support other disabled individuals being failed by the system. I completed my CPR certification and began teaching accessibility awareness classes to first responders, explaining how to assist wheelchair users during emergencies. The four years of lies I had internalized—that independence was a luxury I couldn’t afford—were demolished by the overwhelming action of 420 bikers who proved I deserved actual accommodation.

“You changed the Hell’s Angels,” Theodore told me during one visit, eight months after our initial encounter. “You reminded me that our purpose is protecting people that society dismisses. That real valor exists in unexpected places.”

The Full Scope of the Impossible

Eighteen months after our initial encounter, Theodore shared the final, profound truth. We were sitting in my shelter, his debt paid a thousand times over.

“I need to tell you something, Ethan. Something about that day at the bus shelter that I haven’t shared with anyone except Maggie and Dr. Hammond.” He looked at me with an intense gaze. “According to the EKG, my heart stopped for ninety seconds. Full cardiac arrest. You performed CPR without realizing it. But that’s not the extraordinary part.”

I waited, breath held.

“The extraordinary part is that you performed one-handed CPR while maintaining your balance on a wet bench, using only your upper body strength, compensating for total lack of core stability—and you did it continuously for ninety seconds until my heart restarted.”

I felt my blood run cold. “That’s impossible. CPR requires specific compression depth and rate. It requires core stability to generate proper force. It requires conditions you couldn’t achieve sitting on a bench in the rain, paralyzed from the waist down.”

“I know,” Theodore confirmed. “Dr. Hammond confirmed it’s medically improbable. But you did it anyway. You accomplished something that shouldn’t have been physically possible because my survival required it. You transcended your body’s limitations through sheer determination.”

“I don’t remember doing CPR,” I whispered. “I just remember putting my hand on your chest to check your heartbeat.”

“Your instinct understood what your conscious mind didn’t recognize. You felt my heart stop and you responded with compressions that, technically, you shouldn’t have been capable of performing.” Theodore leaned forward, his voice a hammer of conviction. “Do you understand what this means? It means that disability doesn’t define capability. It means that perceived limitations are often environmental rather than inherent. It means that you accomplished something impossible because you refused to accept that it was impossible.”

This revelation became the philosophical core of my advocacy. I realized that my most dangerous barrier wasn’t my physical condition, but the social construction of disability—the belief that my body defined what I could achieve.

The Legacy Multiplies

Years accumulated. I was accepted to all seven colleges I applied to, choosing Portland State University for its disability advocacy programs. The Hell’s Angels Scholarship Fund covered tuition, housing, and all accessibility-related expenses. Theodore attended my high school graduation, watching as I delivered the valedictory address, focused on compassion, capability, and the ways one rainy afternoon had transformed multiple lives.

“The world told me that my wheelchair defined my limitations,” I told the audience, my voice steady. “That paralysis determined what I could achieve. But Theodore Morrison and the Hell’s Angels proved otherwise. They demonstrated that value exists independent of physical form, that capability transcends able-bodied expectations, and that the most important humans are often the ones society overlooks.”

I graduated college and eventually became the Executive Director of the Thunderhead Accessibility Initiative, expanding its reach nationally and then internationally. Theodore’s health remained stable for five years after the cardiac episode, his medications adjusted, his life dedicated to the Initiative. When he finally passed away peacefully at 76, surrounded by family and brothers, his legacy was secured through the organization that bore his nickname.

I spoke at Theodore’s funeral, addressing hundreds of Hell’s Angels members who had gathered to honor their founder. I wore the leather jacket he had bequeathed to me, the patches a testament to decades of brotherhood and commitment to protecting the vulnerable.

“Theodore Morrison saved my life,” I said, my voice heavy with grief. “Not just by building me a home, but by proving that disability doesn’t define value, that wheelchair users can be heroes, that the world’s messages about limitation are lies designed to maintain systems excluding difference.”

The Hell’s Angels honored Theodore with a motorcycle procession that stretched for miles—420 bikes riding in formation through Portland streets, their thunder echoing the midnight roar that had first woken me years earlier. I rode in a specially modified sidecar attached to Victor Chen’s motorcycle, feeling the vibration of the engine, the familiar thunder.

The procession paused briefly at the bus shelter on Powell and 82nd. I rolled my wheelchair to the bench where I’d sat with a dying stranger, where I’d made the impossible choice. The rain was falling again, Portland rain, persistent and cold. I remembered Theodore’s voice, his promise, and the incredible, cascading response.

Thirty Years of Debt Paid Forward

The decades continued. My hair grayed at the temples, my wheelchair upgraded. The Thunderhead Accessibility Initiative expanded until it operated in 42 countries, employed 300 people, and distributed tens of millions of dollars annually. But I never forgot the porch, the rain, or the moment when everything changed. I kept the original tarp that had covered my sleeping space, preserved in a frame in my office. I wore Theodore’s worn leather jacket to speaking engagements and disability rights conferences.

And every October, on the anniversary of that rainy afternoon, I returned to the bus shelter.

This October, the 30th anniversary, I came alone. I rolled my wheelchair to the bench where Theodore had been dying, where impossible CPR had been performed, where one choice had cascaded into three decades of transformation. The rain was falling, of course.

I sat in the rain, remembering the cold, the desperation, and the sheer audacity of leaving my wheelchair. “We did good work, didn’t we?” I said quietly, speaking to Theodore’s memory.

A younger voice responded from behind me. “Are you Ethan Cooper?”

I turned to find a teenager in a wheelchair, maybe fifteen or sixteen, slight and uncertain, wearing clothes that looked third-hand and inadequate for the weather.

“I am,” I confirmed.

“I’m Marcus. Marcus Thompson. I’m in foster care and my caseworker said I should meet you. Said you might understand what it’s like. She said you used to sleep on a porch before the Hell’s Angels built you a house.” The exhaustion in his voice transcended physical fatigue.

Thirty years. Thousands helped. But the work continued. Systems remained inadequate. Foster care still failed disabled children.

“I did sleep on a porch, Marcus,” I said gently. “For eight months, because the foster care system couldn’t find accessible housing. It was hard, really hard. But circumstances changed, and I want to help your circumstances change, too.”

Marcus looked skeptical, hope beaten out of him by reality. “How?”

“The Thunderhead Accessibility Initiative funds housing modifications and supports disabled foster youth. We can work with your caseworker to find proper placement or modify your current housing. We can provide equipment, advocacy, whatever you need. You don’t have to sleep on porches. You don’t have to accept inadequate housing. You deserve better.”

“Why would you help me?”

“Because someone helped me when I needed it most. Because compassion multiplies. Because thirty years ago, I saved a stranger, and he responded by building me a home. And I’ve spent every day since trying to extend that kindness to others.” I moved my wheelchair closer. “You matter, Marcus. Your needs matter. Your comfort matters. And I’m going to make sure you get the housing you deserve.”

Marcus began crying—the kind of profound, overwhelming relief that speaks louder than words. I understood that relief intimately. I gave Marcus my card and promised to coordinate with his caseworker immediately.

I watched him roll away, slightly less burdened, carrying a fragile, new hope. That was the real legacy. Not the international organization, but the next disabled teenager who wouldn’t have to sleep on a porch. The cycle of compassion was still turning.

I had left my wheelchair in a rainstorm to save a dying stranger. In return, I’d received everything: shelter, purpose, and the understanding that my value transcended physical form. And I’d spent 30 years multiplying that gift, proving that one choice could cascade into transformation measured in decades and continents and thousands of lives improved.

Sometimes salvation arrives in unexpected forms. Sometimes hope looks like 420 motorcycles. Sometimes transformation begins with a paralyzed teenager deciding that someone else’s suffering matters more than his own comfort. But always, always, it requires choosing compassion, choosing action, choosing to believe that we’re responsible for each other.

The rain continued falling. I remained on the bench, remembering Theodore, remembering the shelter, and planning Marcus’s housing modifications. The work was never finished. The need never stopped. But neither did the response, the daily choice to see suffering and act, to build the world that should exist rather than accepting the world that does. One choice, one rainy afternoon, 30 years of cascading consequences. And somewhere, somehow, Theodore Morrison was watching, satisfied that his debt had been paid and multiplied.

News

THE THUMB, THE FIST, AND THE FUGITIVE: I Saw the Universal Signal for Help from an Eight-Year-Old Girl in a Pink Jacket—And Our Biker Crew, The Iron Hawks, Kicked the Door Down on the Kidnapper Hiding in Plain Sight. You Will Not Believe What Happened When We Traded Our Harley Roar for a Silent Hunt in the Middle of a Midnight Storm.

Part 1: The Lonesome Road and the Light in the Gloom The rain, tonight, wasn’t a cleansing shower; it…

The Silent Plea in the Neon-Drenched Diner: How a Weary Biker Gang Leader Recognized the Covert ‘Violence at Home’ Hand Signal and Led a Thunderous, Rain-Soaked Pursuit to Rescue an 8-Year-Old Girl from a Ruthless Fugitive—A Code of Honor Forged in Iron and Leather Demanded We Intervene, and What Unfolded Next Shocked Even Us Veterans of the Road.

Part 1: The Silent Code in the Lone Star Grille The rain was not merely falling; it was assaulting…

THE THIN BLACK LINE: I Was a Cop Pinned Down and Ripped Apart by Vengeful Thugs Behind a Deserted Gas Station—Then, Six ‘Outlaws’ on Harleys Showed Up and Did the One Unthinkable Thing That Forced Me to Question Everything I Knew About Justice, Redemption, and Who Truly Deserves the Title of ‘Hero.’ The Silence of Their Arrival Was Louder Than Any Siren, and Their Unexpected Courage Saved My Life and Shattered My Badge’s Reality Forever.

PART 1: THE TRAP AND THE IMPOSSIBLE RESCUE The sound of tearing fabric and suppressed laughter filled the still air…

The Million-Dollar Mistake: How My Stepmother’s Greed and a Forced Marriage to a ‘Poor’ Security Guard Unveiled a Shocking Secret That Transformed My Life Overnight and Humiliated My Spoiled Stepsisters

Part 1: The Shadow of the Black SUV The heat radiating off the asphalt felt oppressive, a physical burden…

THE SILENT BARRIER: How a Nine-Year-Old Girl’s Desperate Plea to a Wall of Leather-Clad Bikers on a Sun-Blazed American Sidewalk Instantly Halted a Predatory Stepfather’s Final, Terrifying Move—The True Story of the Moment I Knew Heroes Don’t Wear Capes, They Wear Iron and Keep a Vow of Silence That Saved My Life.

Part 1 The heat that afternoon wasn’t the kind you could just shake off. It was the heavy, suffocating…

I Watched My Entire Future Crumble on the Asphalt, Missing the Medical Exam That Could Have Saved My Family, All to Save a Dying Hell’s Angel Covered in Blood and Regret. You Won’t BELIEVE What Happened When 100 Bikers Showed Up at My Door the Next Morning. This Isn’t About Sacrifice—It’s About the Day I Discovered That the Real Angels Don’t Wear Scrubs or Suits, They Wear Leather, and They Were About to Change My Family’s Life Forever.

PART 1: The Asphalt and the Admission Ticket My hands were shaking, but not from the chill of the…

End of content

No more pages to load